Meeting Beton Ltd.

Place: Ljubljana

Date: May 3-5, 2018

Travel time: 5 minutes bike, 4,5 hours train, 12 hours bus, 3 hours car

Meeting time: 15 hours

Reading time: 25 minutes

Dear Branko,

Dear Katarina,

Dear Primož,

Sitting on a terrace in front of the SEM, the Ethnographic Museum in Ljubljana, protected from the raindrops on a warm day in spring, I ask if you ever feel like living in a bubble. It just comes without thinking, with all the people coming and going, greeting, discussing current affairs on a casual Friday morning: I have the feeling that you know everybody, that Ljubljana is a very easy place to live and that you’re right in the middle of it.

It actually started already on the bridge between the bus station and the railway station in Venice, where we first met. We exchanged some emails before. I texted you from the train. And then we met, there, on that Venetian bridge, surrounded by hundreds of tourists. I immediately knew it was you, the three of you. It was easy. You’re a collective. You’re actors. You have attitude.

We went for a coffee and chilled. Greeting, discussing, chilling: that’s what we did when we met. We all had a short and eventful night behind us. You, finishing your residency at the Santarcangelo Festival, discussing with the director until late at night. Me, sitting on a very uncomfortable bus between Paris and Milan. We continued chilling in the car. I felt like becoming part of the family. The lack of sleep gave us a shared history. A shared destiny also: to chill. We talked, shared experiences, ideas, plans for the days to come. I was really glad being there with you in the car, and not having to travel for another five or six hours by train and tram via Trieste to Ljubljana. Things became so easy.

*

Before leaving for Ljubljana, Ilse – the Imagine 2020 coordinator in Brussels – told me: “don’t forget May ’68”. It’s fifty years ago now. You have to know that this Grand Tour was originally planned to take place in May and June 2018 (in the end I decided to start the Tour in February, so I’m already over halfway now). That has everything to do with the spirit of May ’68. What’s left of the spirit of ’68? Can we recognize something of that in what happened with the Occupy movement? In the Arab Spring? In Athens or Madrid? Or in the social movement against Macron, maybe? The most important European revolt of the moment, that is deliberately and totally neglected outside of France. It remains to be seen. All I know is that my first stop on my Grand Tour in this warm (too warm) month of May of the year 2018 was Paris, where only two years ago the spirit of May ’68 seemed to come back to life with Nuit Debout, the gathering of students and workers on Place de la République. Was it like that in ’68? I remember their slogan: Rève Générale. They took out the G of Grève, and instead of a general strike, they got a general dream. I remember their calendar, starting on March 31 and counting on from there, just like during the French Revolution of 1789. It was beautiful, it was promising, it made me dream, and then it disappeared. Like so many movements that mark the beginning of the 21st century. As if everything comes and goes all the time.

I didn’t have to look far to connect to the spirit of ’68, the spirit of revolt, coming to Paris on this warm, too warm, day of May 2018. It came to me at the Gare de Lyon, while I was waiting for the night train to Venice, to meet you. It started with a magazine: Les Inrockuptibles. I’ve been reading the magazine on and off for about thirty years now, following what goes on in the world of music, arts, cinema, literature. Sometimes it makes me feel old, sometimes it helps to stay young. I don’t buy it so often anymore, but this issue I bought because Les Inrocks invited the young French writer Édouard Louis to be editor-in-chief for the occasion. Was it a coincidence that they invited him for their first issue in May?

I very much liked Louis’ first two books, pour en finir avec Eddy Bellegueule and Histoire de la violence. The invitation from Les Inrocks coincides with the publication of his most recent and third novel Qui a tué mon père: who killed my father. I bought that too, while buying the magazine. The question on the cover of the book leads to the central question in the magazine: where is politics? In the book he writes the history of his father, who went working in the factory at a very young age, got seriously injured by an accident and ends up, at fifty, cleaning the streets in a small provincial town. For Louis it is clear. The answer to the question “who killed my father?” is: politics. The answer to the other question – “where is politics?” – is: there, in his father’s living room. That is where politics are felt first. There, every new election, every new government, every smallest change in the social security legislation is felt like an earthquake. Politics is made, but not felt in the cabinets of Parisian politicians. Nor in the books of Parisian writers. Nor in theatres across Europe. We all live our own bubble.

That’s what I was thinking there, sitting on a bench in Gare de Lyon, waiting for the night train from Paris to Venice. Until I saw a little icon appearing on the board announcing the trains and tracks in the station. Instead of a track number, it showed something that looked like a tiny bus. I knew about the strikes of the French railway workers. It started in March. Every five days they strike for two days. They have a calendar, just like Nuit Debout, announcing all the days of strike. I checked it before I left. This weeks strike would be on May 3 and 4. My train leaves on the 2nd. But I forgot to think about the fact that it was a night train, that it also rides on the third. I realised I was fucked. Was I getting closer to the spirit of ’68 that Ilse referred to? I didn’t have to try hard to feel politics, getting on the bus to Milan, where we would continue by train to Venice. I physically felt politics, on an uncomfortable seat in an uncomfortable bus. I could have been rocked asleep in a bed in a train instead. I tried to think about the striking railway workers. About their cause. About the importance of having a good functioning public railway system as a basic good. And I felt like in a bubble, trying to figure out what the other people on the bus – the actual bubble I was in – were thinking. Who were they blaming for their situation? Were they also searching for a way to make this discomfort meaningful? Were they revolting yet? Was I revolting, actually?

In the nice and easy bubble of the car (Primož at the wheel brought back reminiscences of a journey to Slovenia, twenty five years ago, just after the independence when there were seemingly no rules yet – or anymore – on the highway and everybody was driving anywhere and anyhow they could; I never felt such freedom and such danger combined as then) you explained me some things about the upcoming project you started working on during your Santarcangelo residency last week. I understand it’s about education. It’s about the future generation. You want to turn the next generation into revolutionaries.

And there is my question again: where is politics? I still have the feeling we’re not getting out of our nice and easy and comfortable bubbles yet. That we’re still not feeling politics, like the father of Édouard Louis does. That we’re playing a game of representation, like the politicians do. That is also what you do, as theater makers, of course. You delegate questions that were initially addressed to yourself to your audience and, in this case, to the next generation. Why do you want them to be revolutionaries? To be prepared for the catastrophe that will come and that is caused by former generations. As if you want to blame them first so they cannot blame you afterwards for the situation they are in. You start creating a future fiction wherein the children will have no other choice than to be revolutionaries. That is also the problem with global warming: the problem isn’t bad enough yet to act in an adequate way. We know that something in former generations went wrong, but we don’t know what to do yet. We don’t really know – or want to know – what the problem is yet. To know that, we will have to get out of our comfort zone, out of the bubble. Politics is tangible there already. All we have to do is acknowledge that global warming is a political problem. Instead, as Katarina said, we prefer to rely on technology to create a solution while at the same time creating a distance from the problem.

We don’t know yet what to fight for. What is at stake? The other night, while watching Interstellar on TV, a Hollywood blockbuster about humanity in search of another planet to survive after the catastrophe, the question that came back to me all the time was: why do we need humans? It is difficult to say goodbye to our human selves as a person. But why do we need humans as a species? And I thought: we just don’t want to be the last one on earth. We don’t want to be the last person on this party. That is why we need humans. That’s what we need for ourselves. But for the planet? We only need biodiversity. And that is exactly what is disappearing because of humans.

*

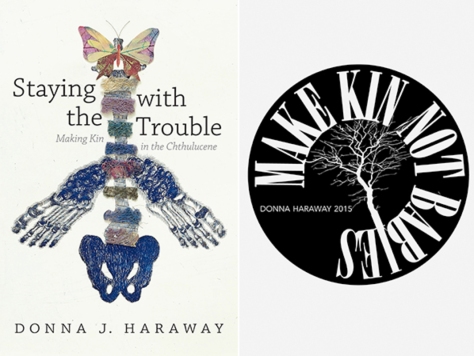

You are a collective. You work together, as a family, creating an extended family around you. There is Maja from Bunker, not only a partner of Imagine 2020, but also producer of all your plays. There is Jure taking care of the sound design, Mateja for the costumes, Urska for the dramaturgy and Toni for the photos and set design. It makes me think of Donna Haraway who, in Staying with the trouble – making kin in the Chthulucene, explains her view on the future of family. Her motto is Make kin, not babies. We do not need to procreate to have family: population explosion solved. We even don’t need humans to make kin. She makes kin with her dog, there are people who adopt trees, you can make kin with a mushroom, or the bacteria in the living network that is your body. Being-with is the technique Haraway develops for an ecological life – her technique to stay with the trouble. We don’t need more humans, rather less. We need to care for what is already there and for what will come.

Being-with is also what I would propose today instead of revolt. It has something to do with age. There was a time when all I wanted to do was revolt and do things different than the people who came before me: my parents (that is also where things started for Édouard Louis). But, looking back on that revolt, you’ll quickly notice that you start doing exactly the same thing as the people you’re revolting against. What you want is what they have. Édouard Louis wanted to be as strong and masculine as his father. I wanted to lead a life as hedonistic as my father. That is what you have to realize before taking a distance from your family, a real distance, to become yourself and start making kin. Like Édouard Louis with his newly made friends in the intellectual circles in Paris where he lives now, lightyears away from the village where he was born. Or like me, in Brussels, with my newly made friends in the cultural circles where I live. From there you can go back to your family, like Édouard Louis does, meeting and reconciling with his father after many years. Then family members become kin, between your friends and other living things around you. That is the moment you start being-with and can stop revolting against what eventually you will learn to be-with after all.

Primož told me about a documentary, you watched together as part of your research for the new piece. The title is Swedish Theory of Love. It is about a social experiment in the seventies. The idea was to make people independent from each other, without any family ties, to allow other forms of relations instead. Children don’t have to care for their parents and vice versa, because the government would take care of everything instead. They even installed the largest semen bank in the world to free women from men. But people got completely isolated. As a result, there is an agency now, searching for dead people, so isolated that nobody knows they are dead. No relatives, no children, no friends or neighbours. They found people dead for over a year in apartments while the rent, the bills, everything continued to be paid automatically. What started as an emancipatory process, freeing people from ties that were considered conservative, actually lead to a very unhealthy situation of total isolation.

This is how you do research. It starts from a very banal idea – to educate revolutionaries – that you then try to turn into a reality. Katarina used the term proactive theatre. That is how I think I can understand your plan to work with this new generation that is not there yet: you act proactive. Like the Swedish government did in a way. Instead of working with a problem that is already there, you anticipate on problems to come. And actually, I think, your problem with the new piece is that there is no problem. Not yet. Or that you want a cure in the future for a problem that has to be solved right now.

It’s like with the scientists that Branko mentioned who in 1968 had to write about the world in 2018. Their vision of new forms of communication, where images would be more important than words, prefigured the internet. But at the same time, none of these scientists could imagine the cold war to be over in fifty years (it turned out to take hardly more than twenty years). And when one of the scientists said that there would be 5 billion people on earth he was confronted with total disbelief. Today we are nearly 8 billion. There it becomes clear how the scientists create problems and solutions, starting from wrong presumptions.

It is so difficult to talk for somebody else. Especially when that person is not there (yet). I can not tell someone to take a train and, in case of a strike, to sit on a bus for 12 hours. I can decide it for myself, and then I can create a story around it with the strike and Macron: a story about the collective, about the importance of public transport as a common good. That is where I want to take it to another level. That of politics. But there too, politicians have to learn thinking about themselves. They have to position themselves in the place of the other. Of the father of Édouard Louis. Of the next generation. Politics is making projections of the future: you have to include yourself in that projection. That is the symptom you try to deal with in your new piece. There lies the friction that needs to be solved: you have to think for yourself as well as for the next generation that is already part of your world, while it is still growing. So like biodiversity, maybe we have to learn to think generationdiversity. We are not alone, there is always a generation before and after us.

Branko referred to Slovenian theatre in the eighties, saying that good art comes when there are real problems. When there is oppression, there is resistance to that oppression. So maybe, if you want to do something good, you should rather create a really, really bad situation for the next generation. Create something that they could express well, that they will know what the problem is. But again: what if there would be another form of revolt? What if, instead of coming up against something, we tried to be-with something? What if instead of revolting, we would go with the flow? Try to follow what is going on. That is how I like to work with the future generation. I like to enter their world and invite them to enter mine. It is what I learned from Jacques Rancière’s Ignorant Schoolmaster who has to learn the language of his students (well, actually he managed to make them learn his language) in order to teach them. That is how he can teach what he doesn’t know: by passing on the tools to learn, instead of the content. And that is how we have to learn to deal with the future generations. Or, talking about ecology, because that is where we always come back: you have to learn to go with how things go, to follow, instead of revolting against your environment. We should go with nature and go with culture instead of revolting. Be concerned. That is what it means to be emancipated. To see things – not only people – as if they are all on the same level.

*

The idea of generations is something that often comes back in this Grand Tour while talking about art and ecology. Ecology is something that’s passed on from one generation to the other. It is always the same thing, based on the idea of care, but always in different circumstances. When I look at your work, I get a similar feeling: that you’re always doing the same thing, but under different circumstances. You deal with doubt, with self questioning, self persuasion, identity. The same things come back when you talk about education, adolescents: doubt and anxiety. You never know what will become of your work. Like a forester planting a tree of which he can only see the result in thirty years. But always he has an idea of what will come, based on future experiences.

You are at a point in life – you’re all in your forties: in fine arts we call that mid career – where you have learned through experience to predict what will come and can pass on that experience to future generations. You even considered engaging three young actors to replace you as apprentices who can do things you’re not able to do anymore. A joyful dance full of energy, for instance, or going completely into the subject without thinking. In 2012 already, with I say what I’m told to say, you were talking about your own generation. Today you’re working with the next one. In So far away – introduction to ego-logy (2010) you asked yourself if you should penetrate reality or stay in the theatre. You went out in the street to shoot a video for the performance. There you start mixing things up: theatre and real life, fact and fiction. That is something that comes back very often in my Grand Tour, this mix of fact and fiction, this need for new stories – fiction – to deal with reality. That is also why philosophers as Bruno Latour or Timothy Morton work together with artists as Philippe Quesne – a theatre maker – or Olafur Eliasson – a visual artist. They use art to create a new framework for thinking and to create fictions. That is what you deal with in your performance from 2013, Everything we’ve lost while we’ve gone on living, about coming of age in different time periods – the seventies and the nineties – about generations and about stories. Fiction, that’s what you’re aiming at, through memories of what was and projections of what is to come.

The seventies: a time of crisis when people could still believe in the future. The nineties: a time of opportunities with the fall of the wall and new nations coming up for themselves. Just do it! was the slogan of that time. In the end there is not such a difference between the belief in the future of the seventies and that of the nineties: from paradise to disaster, revisited. And then I think, twenty years later, in the second decade of the 21st century, about the new hope that comes to rise in the disaster we are living. I have to think of your national philosopher, Slavoj Žižek, still defending the idea of communism to reinvent a shared society that is also a product of the nineties. That is how Everything we’ve lost while we’ve gone on living becomes like an after party in the nineties on the ruins of the seventies.

Or look at Ich Kann nicht Anders (2016): that too is an after party. I cannot resist to read it as a trash version of American Psycho, for a new generation, 25 years later. There too you have these two worlds colliding – the very civilized world of the business men in their suits, going to restaurants and discussing menus and business cards, talking in quotes as if their words come right out of glossy magazines and on the other hand the very dark side with the murder and sex scenes. You could also say that it is about the individual and the collective, but always with this one image, this one icon, as an example: Donald Trump. The characters in American Psycho are all mirror images of Trump. That is how individual it is and that is how individual you are in Ich Kann nicht Anders. That play is about a bubble and the difficulty – or even: danger – of escaping it. About the audience entering your world. The absence of a stage brings them really very close, the moments you take of your clothes make it very intimate.

Katarina explained me how she looks at Beton Ltd. as a thinking platform. No craftsman methodology, but thinking about content, context and staging all at the same time. It is a bubble, an ecological system on its own, but there are openings to the outside. It starts with the dramaturge, the set designer, the musician. It continues with the people like me or the director of Santarcangelo, who come, invited or not, to discuss your work. The question then for me is how far does the collective go? How do you deal with vagueness for instance? Do you use the vagueness of your performances – that are not always very clear – as a tool to finish the play? How far does the family go? There are probably also people in the audience that come back to your performances with questions or remarks. That was also the feeling I had the evening when Branko and me went to see Katarina perform in another play. We had to pay for our free tickets: there are too many insiders – friends, family, colleagues – in the audience to hand out all these invitations for free. I think this exchange with the ‘family’, the proximity of the people in the audience, is very important. There it becomes social art, finding ways to engage people, of doing things together. There you get something like a methodology. Close to a therapy. Like with your idea to invite three young actors to take over your role on the stage. Isn’t that a way to open the bubble? To take the risk? It is a way of sharing things. It is a political gesture. Putting yourself in a position in between.

Education is what happens in between. Ecology, emancipation: it all happens in between. Being in between is also part of the DNA of Beton Ltd.: the performances you make every two years as a collective, come in between your work in the institutional context of theatres or schools. You are shifting places there. From the institution to the collective, from the main stage to the living room, from the personal to the political. You become someone else. That is what happened when we went to see Katarina perform in the other play. Branko was sitting next to me, knowing that I didn’t understand a word of what the actors were saying. I had a print of the English translation in my hand, but could not use it because it was too dark. So I had to look, without listening. That is, he told me afterwards, what Branko was doing too: looking without listening. He had already seen the play before, so he could allow himself to do that. But while doing that, he became other, he displaced himself into my position. This, I think, is what we should do. Instead of revolting, we should put ourselves in the place of the other, try to think with the other, or with what is other. This is also what Katarina’s play was all about (I know that by now, because I read the translated dialogues afterwards): about displacing yourself in the position of the migrants that were planned to come and live in a school in a Slovenian village and into the position of the people who live in the neighbourhood of the school, revolting against the coming of the migrants.

After our meeting, I took the train to Zagreb to meet Tamara Bilankov. There I found this sign by the window: È Pericoloso Sporgersi. It is dangerous to lean out. It’s a sign from another time. It’s one of the first phrases I learned in Italian, as a kid, taking the night train to Switzerland for snow class. It’s from a time when you were still able to open the windows in the train. Today, train windows don’t open anymore. Even in the train where I found the sign, the windows were replaced by new, hermetically closed ones. For our safety and for the sake of air conditioning, trains become bubbles with no connection to the outside. I had to think of this scene in Ich Kann nicht Anders where Katarina, very casually climbs on the windowsill as if she wants to take some fresh air. And then she jumps. First you think it’s a tragedy – a hilarious one – but a few minutes later, when she walks in again through the door next to the window, as casual as she climbed on the sill, it turns out to be a farce. You feel shock and relief going through the audience. And that’s how theatre works. It’s a bubble, but there are ways to break it and connect with the reality of it. That’s where theatre can still be dangerous.

Did I tell you about the window in my hotel room? It’s on the sixth floor and it didn’t open. For security reasons. Or, actually, it did open, but only ten centimetres or so. There is a warning by the window, to shut of the airco before opening. It fits the not very inviting slogan of the hotel: Go Green or Go Home. (When I read that, I want to revolt and rather turn on the airco before opening the window.) It also fits the image of Ljubljana as ecological capital in 2016. Or the image of the different garbage collectors in the streets: for organic waste, for paper, for glass, for plastic and cans,… That is also part of the bubble of the city you live in. The city I hardly recognize from 25 years ago. The biggest difference probably is tourism (how ecological is that?). Meeting my friend Koen, whom I helped moving from Brussels to Ljubljana 25 years ago and who is now programming director at Ljubljana’s Kinodvor, I learn a new thing about bubbles. Twenty five years ago he moved here because he fell in love with a dancer. At that time the cultural world was much more mixed, he says. People went to theatre and cinema. Today every discipline has its own bubble. But there is hope. The day before we met, Koen had a meeting with the women from Bunker. They make Ljubljana easy. Bunker will work together with Kinodvor on the new project of Milo Rau, a theatre maker in Ghent, whose new project consists in a film and a theatre piece. So there is still hope. Let me tell you, my friends: the times they are a-changin’.

Thanks for having me in your world, even for a brief moment of time. I hope it changed too. Thanks for opening your bubble and letting in the danger.

Keep in touch,

Pieter